Mapping algorithms to custom silicon - Part 1

An introduction to the messy middle between software and microarchitecture

Disclaimer: Opinions shared in this, and all my posts are mine, and mine alone. They do not reflect the views of my employer(s) and are not investment advice.

Unless you have been living under a large silicon wafer, you would have heard some version of “custom silicon is the future.” In an earlier post, I attempted the classification of this exploding set of XPUs. While classification would help someone understand how to best match today’s chip with today’s algorithms, the real billion dollar question (literally) is: how can we ensure that tomorrow’s chips are best suited to run tomorrow’s algorithms.

One of the biggest problems in hardware-software co-design is that hardware and software have always existed on separate islands. So, the right way to answer this question is by bringing the two a little closer. In that spirit, this post (and hopefully many more to come) is the result of my collaboration with Avik De. Together in this post, we explore the “messy middle” between algorithms and silicon.

The push and the pull

To make custom silicon work, it needs both a “push” and a “pull”. There is a “push” from the side of the hardware designer (who we will call Harry) to get more developers to use their chip, and a “pull” from the algorithm writer (who we will call Alice) to find the best platform on which to run their software.

The algorithm writer (Alice) wants to be able to frame their algorithm in a high-level language. This algorithm could be anything, ranging from the numerous advancements in machine learning, to algorithms from emerging domains like robotics. Although Alice is confident about the value of her algorithm, she is unaware of the best hardware architecture to run it on. This is the “pull” - Alice needs to be able to find hardware to run her algorithm while staying within her software ecosystem of comfort.

Harry, on the other hand, has a great idea for a power-efficient way to compute matrix products by optimizing the operations, the instruction overhead, or the memory movement. He develops the design and synthesizes it on an FPGA. He knows it’s better than any other hardware architecture out there, but he has no idea how to get people to try it. This is the “push” - Harry wants to get his ideas out there, but needs to bridge it to Alice’s “pull.”

In theory, this looks like a match made in heaven - can’t Alice just take her algorithm and “run it” on Harry’s chip? Well, not quite, because of an idea that has been around as long as computing, but continues to be challenging.

An old analogy

The idea that Alice should be able to “just run” her code on Harry’s hardware is not new. In fact, it is the idea that made general-purpose computing work. A CPU solves this problem using the idea of Code Abstraction.

Say Alice was mapping an algorithm to run on a general purpose CPU - she would simply write the language using a high-level language like C++ or Python, “compile” this code, and run it on an x86 or ARM CPU. The reason why this process is so simple is the emergence of the idea of an Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) - which in simple words is a contract to map high-level languages to certain general purpose hardware. (This post skips the details of ISA and compilers, but if you are interested, check-out this older Chip Insights post.)

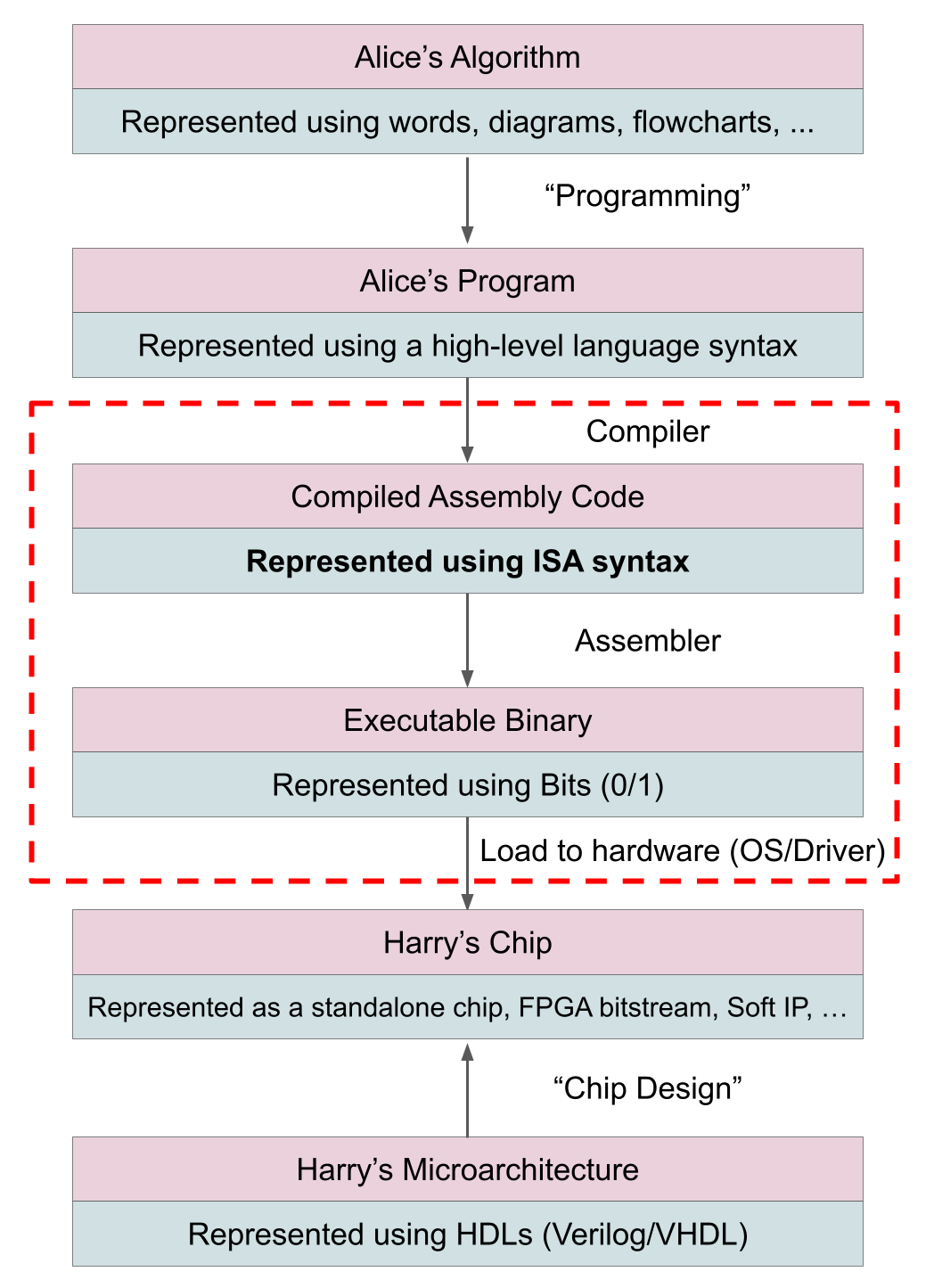

The mapping between Alice’s algorithm and Harry’s hardware using a standard ISA can be understood using this diagram:

One of the key advantages of specifying an ISA is that it allows software developers to write code that can run on evolving hardware without needing to know the specifics. Say Alice compiled her algorithm using an x86 compiler like GCC, when the next generation of x86 CPU is released, she will have to do one of the following:

In majority of the cases, as the hardware microarchitecture improves, the same binary can benefit from improvements without needing to be rebuilt.

Even if a major hardware improvements need to be accompanied by changes to instruction encoding or order (for example, Advanced Vector Extensions (AVX)), it is managed by “the compiler” - Alice simply needs to recompile the same high-level language code with the latest version of the compiler in order to enjoy the benefits of the new and improved hardware.

This separation worked spectacularly well, because:

Hardware designers like Harry innovated on pipelines, caches, branch predictors, and out-of-order execution.

Software designers like Alice largely ignored those details and built software that lived for decades.

Compilers absorbed the complexity at the boundary.

However, custom accelerators break this assumption.

Why isn’t there a standard ISA for custom silicon?

In the early days of CPUs, every CPU provider had their own custom ISA, largely because hardware constraints and software ecosystems were still tightly coupled. Over time, a few winners emerged, leaving us with just 3-4 significant ISAs, each supported by mature compilers and software ecosystems. This convergence was possible because general-purpose programs share a common structure: scalar control flow, pointer-based memory access, and relatively uniform performance characteristics across workloads.

There is a common misconception that custom accelerators would evolve in the same way - that over time, a standard ISA would emerge, and every accelerator would support it. But this idea is fundamentally flawed. To truly understand why a standard ISA cannot exist for custom accelerators, let’s consider a thought experiment. Assume that Harry defines a standard ISA for his accelerators. Let’s try to think about how that ISA would look for an operation like matrix multiplication.

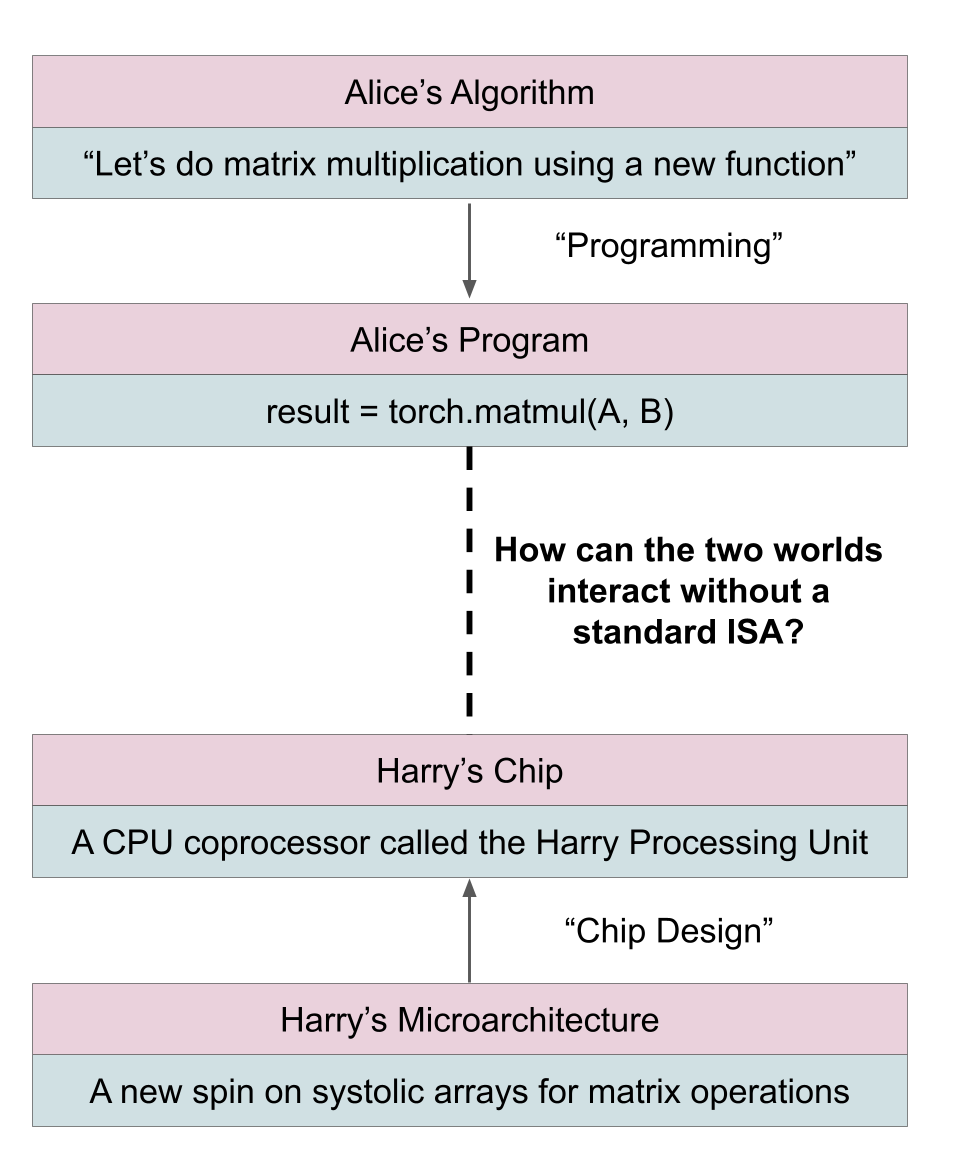

If Alice is using PyTorch, the operation would look something like this:

result = torch.matmul(A, B)

There are certain aspects of matrix A and matrix B that inform Harry how to execute this operation efficiently on his specific hardware. Crucially, these aspects influence not what computation is performed, but how it is scheduled and mapped onto hardware resources. For example, the shapes of A and B can be used to decide:

Tiling strategy: How many chunks should the matrix multiplication be split into based on the available hardware resources

Buffering techniques: what data can be stored in the fast, on-chip SRAM, and what should be moved to DRAM.

Data layout: For the specific size of A and B, is column major better, or does a tiled layout reduce memory accesses?

This is a short list that only considers the matrix shape - several other factors, like the data types, sparsity, etc. can be exploited to map this operation efficiently in hardware.

However, Harry needs to define a standard ISA that encompasses all these possibilities - the same ISA must work for a large square matrix with significant sparsity, as well as for matrices with just a single row or column. The compiler alone is of limited help here, because many of the most performance-critical decisions like tiling, buffering, and layout are instance-specific and cannot be encoded directly into an instruction set contract.

If Harry tries to account for all these possibilities within an ISA, he must either:

Over-specify behavior, resulting in an unoptimized, CPU-style ISA and microarchitecture

Stick to a very low-level abstraction (resulting in bloated hardware - like one large matrix multiplier with huge amounts of memory.)

In either case, a standard ISA would strip away the very benefits that customization is meant to provide. So where does that leave Harry and Alice?

The two bridges

Since Harry can’t simply expose a standard AI ISA and call it a day, the question becomes: how does his hardware connect to Alice’s world at all?

Today, there are two practical bridges between them.

1. Runtime-level integration

In the first approach, Alice expresses her model in a standardized, framework-agnostic format. A shared runtime is responsible for executing that model and deciding which parts run on which device. From Alice’s perspective, almost nothing changes. She writes PyTorch or TensorFlow code and exports a model. From Harry’s perspective, the integration surface is narrow and predefined: he implements support for a fixed menu of operations, and the runtime takes care of everything else.

A useful analogy here is a food court appliance. Alice places an order by pointing to items on a menu: “grill this,” “blend that,” “heat this up.” The food court manager (the runtime) decides which appliance handles which step. Harry builds a specialized appliance that performs certain actions very efficiently. If the order matches the appliance’s menu, the runtime sends the work to Harry’s hardware and it shines. If not, the runtime quietly routes those steps to a different device that knows how to handle them. (which is typically a CPU or a GPU.)

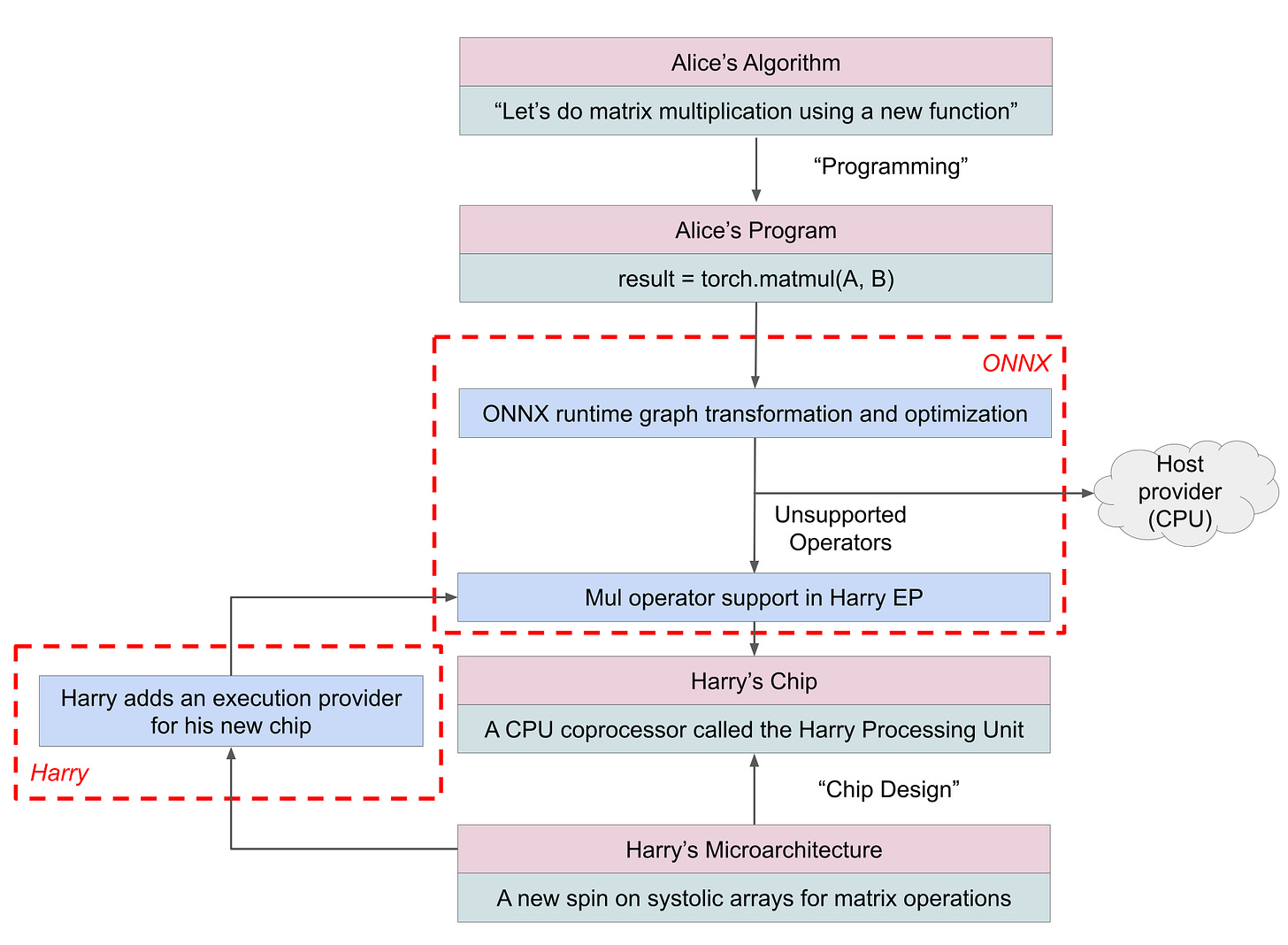

This is exactly how runtime-level integration works:

The model is a graph of predefined operations

Each operation is stateless and self-contained

Control flow and orchestration live outside the accelerator

A concrete example of this approach is ONNX Runtime Execution Providers, where hardware vendors accelerate supported operators while delegating unsupported parts of the model to a fallback device. This diagram explains how Alice’s software and Harry’s hardware can talk to each other using ONNX.

This model works well for inference workloads, where computation is a fixed graph of tensor operations. However, because execution and control flow remain outside the accelerator, it limits how much of the hardware structure (custom memory hierarchies, interconnect flow) can be exposed.

2. Compiler-level integration

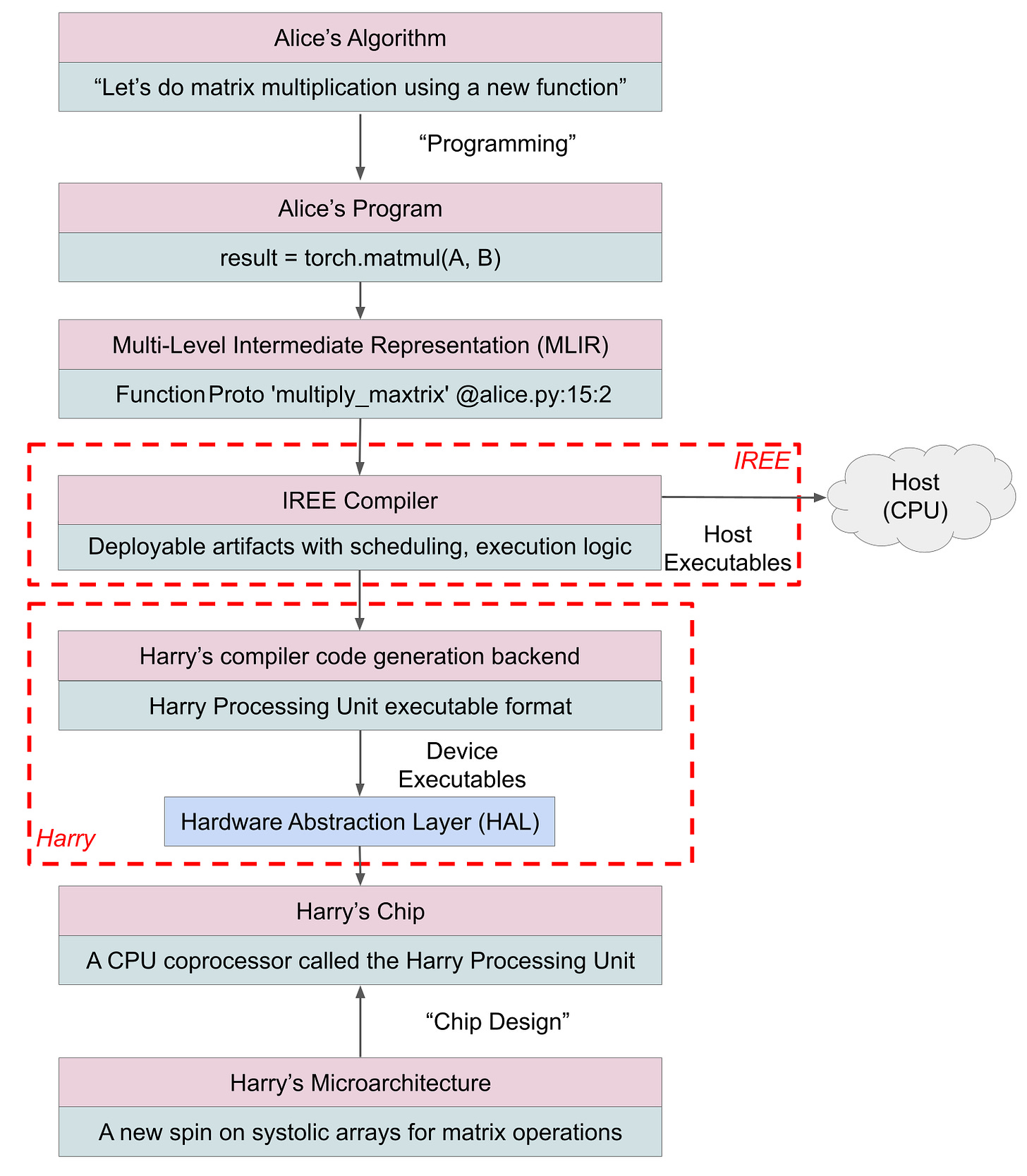

In the second approach, the bridge moves deeper into the stack. Instead of plugging into a runtime API, Harry integrates at the compiler level, where programs are transformed before execution. Alice still writes high-level code, but now the compiler is responsible for mapping that computation onto the hardware - deciding how loops are formed, how memory is reused, and how execution flows on the device.

The analogy here is a custom-built kitchen.

Instead of ordering from a menu, Alice hands over a recipe. Harry designs the kitchen itself: where ingredients are stored, how cooks move, which steps happen in parallel, and how decisions are made mid-cooking. The recipe is compiled into a precise plan tailored to that kitchen.

This may sound similar to targeting a standard ISA, but the distinction is critical. A standard ISA fixes the instruction set and execution model that all software must target, forcing hardware innovation to happen below that boundary. Compiler-level integration, in contrast, fixes only the meaning of the program. The compiler is free to reshape loops, memory usage, and control flow to match the hardware, without exposing a stable instruction set to the programmer. This allows each accelerator to express its architectural strengths without being constrained by a one-size-fits-all ISA.

This approach requires much more effort from Harry, because he must:

define how programs are lowered,

expose memory and synchronization primitives,

and implement a runtime that can execute compiled programs.

But in return, Harry can support:

data-dependent control flow,

irregular or sparse computation,

custom memory layouts,

and long-lived, stateful programs.

A representative example of this model is IREE, which provides a compiler, optimizer, and runtime along with a hardware abstraction layer. Instead of mapping individual operators, Harry defines how programs execute on his device. This turns the accelerator from a co-processor that executes individual operations into a programmable compute target that runs complete programs independently, as shown in this diagram.

It’s worth emphasizing that IREE can ingest programs from multiple frontends, including ONNX, before lowering them through its compiler stack. The distinction between runtime-level and compiler-level integration is therefore not about which framework Alice starts from, but where hardware-specific decisions are made.

Conclusion

We’re entering a phase where meaningful gains in AI performance and efficiency are increasingly coming from custom silicon. But the success of that silicon depends less on raw compute and more on where it connects into the software stack.

This post was intentionally a high-level overview of that connection point. The space is complex, fast-moving, and still evolving, but at a distance, two broad patterns are already visible. Runtime-level integration offers a fast path to deployment by fitting new hardware into an existing execution model, while compiler-level integration demands more effort but unlocks far greater control over how computation actually runs. Neither approach is “better” in the abstract - each reflects a different tradeoff between ease of integration and expressive power.

In the next parts of this series, we’ll make these ideas concrete. On Chip Insights, we’ll walk through building a simple runtime-level backend, starting with a CPU implementation and then extending it toward custom hardware on an FPGA. In parallel, on min{power}, we’ll look at the problem from Alice’s side: how different classes of AI and robotics workloads place fundamentally different demands on hardware, and why those differences increasingly matter.