The Alphabet Soup of Processors

Not sure which will end first: Moore’s Law, or alphabets used to describe processors?

Disclaimer: Opinions shared in this, and all my posts are mine, and mine alone. They do not reflect the views of my employer(s) and are not investment advice.

CPU. GPU. TPU. NPU. DPU. IPU. LPU.

Every year, the alphabet soup gets richer. But I wonder if it’s adding any value? Over the last two years, GPUs were the unquestioned champions of the AI boom. Right now, TPUs are having a moment as the new architecture that is supposedly better for AI than GPUs. NPUs reliably show up during some product keynotes, often accompanied by “inference” or “low power.” Meanwhile, CPUs still have their audience of PC and smartphone enthusiasts.

At this point, the industry’s obsession with new “PUs” is starting to look uncomfortably familiar. We’ve seen this movie before - with process nodes. Once upon a time, node names conveyed real, comparable information. Then they became branding. “7nm” stopped meaning 7nm. “3nm” stopped being smaller than someone else’s “5nm.” The label survived; the meaning didn’t. I think processor acronyms are heading down the same path. Pick a new letter. Add “accelerator,” “custom,” or “ASIC.” Publish a carefully chosen benchmark. Congrats, you have a new processing unit.

The problem isn’t that TPUs, NPUs, or GPUs aren’t important or innovative. The problem is that the acronym leaves out the essence of the architecture: what it’s actually optimized for, what tradeoffs it makes, and where its real value comes from. If you squint hard enough, almost anything can be called an accelerator. If you zoom out far enough, almost everything looks like a CPU. This does not sit well with me.

Continuing with the theme of my last post, I don’t think the right question is “Is this a GPU or an NPU?” It’s whether we’re even using the right vocabulary to evaluate compute architectures at all. Instead of arguing over letters, we should be asking sharper questions - questions that force clarity instead of reinforcing branding. I think the following four questions are a far more informative way to classify chips.

Question 1. Host relationship: Is your product the boss, a helper, or just another block on the die?

Categories:

Standalone: Boots an OS and owns the system.

Co-processor: Lives behind PCIe or a fabric. Needs a host to schedule work, manage memory, and keep the lights on.

Integrated IP: One of many blocks inside an SoC, visible to software only through drivers or libraries.

Why it matters:

Host relationship determines who controls the system. Standalone processors shape the entire software stack and system architecture. Co-processors live and die by host integration and software orchestration. Integrated IP blocks rarely escape the platform they’re embedded in, no matter how impressive the pure-silicon performance is. Two chips with identical compute units can have wildly different impact depending on whether they’re in charge, or waiting for instructions.

Question 2. Domain coverage: How many different major software domains (at least a million developers) can this architecture serve effectively?

To clarify, I consider the following as major software domains of today.

System software: OS kernels, language runtimes, compilers, CLI tools

User Interfaces: desktop/mobile apps, browsers, light graphics

Data processing: SQL databases, analytics, streaming

Media & graphics: Video encoding/decoding, 2D/3D graphics pipelines

High Performance Computing: simulation, scientific computing, linear algebra

ML/AI workloads: training and inference across model families

Categories:

General purpose: The chip is competitive or better than the incumbent across 3 or more domains

Domain specific: The chip excels only in 1-2 domains

Why it matters:

Domain coverage is the difference between platforms and point solutions. General-purpose architectures benefit from massive software ecosystems, long lifetimes, and constant reuse. Domain-specific chips can deliver spectacular gains, but only as long as the workload stays stable. When you are looking at a domain-specific chip, the domain matters as much, if not more, that the silicon innovation. (As Jensen Huang puts it, pick “Zero Billion Dollar” markets.”)

Question 3. Execution paradigm: What architectural feature delivers throughput?

Categories:

MIMD (Multiple Instruction, Multiple Data): Many independent cores, each running its own control flow. Classic multicore and many-core CPUs live here.

SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads): Groups of lanes share an instruction stream with per-lane masking. This is the beating heart of modern GPUs.

Custom: Fixed or semi-fixed dataflow architectures designed around specific computation patterns (e.g., systolic arrays, spatial fabrics).

Why it matters:

Execution paradigm reveals what kind of parallelism the architecture is betting on. MIMD favors flexibility and irregular control flow. SIMT thrives on massive data parallelism. Custom paradigms trade generality for efficiency. Once you understand this axis, performance claims stop sounding magical and start looking like predictable outcomes of design choices.

Question 4. Programmability model: How does a programmer get work done from your chip?

Categories:

Native ISA: General-purpose compilers (C/C++) target it directly.

Kernel-compiled: You write kernels in a language extension like CUDA, OpenCL, HIP, or a domain-specific language.

Graph-compiled: You describe computation as a graph (often via an ML framework like PyTorch or TensorFlow), and a compiler maps it to the hardware. In graph-compiled systems, the graph is the primary abstraction for the programmer, not the kernel. (Graph-compiled systems still use kernels underneath.)

Bitstream configured: You configure the hardware fabric itself. For example, FPGA bitstreams or CGRA configurations.

Why it matters:

Programmability determines who can use the hardware and how fast ecosystems form. Native ISAs scale with developer count. Kernel models reward specialists and expert programmers. Graph-based systems trade flexibility for convenience: they work extremely well when your problem fits the graph, and poorly when it doesn’t. Bitstream-based approaches offer ultimate hardware control, but at the cost of accessibility. Many promising architectures fail not because of silicon, but because the programming model never escapes a niche audience.

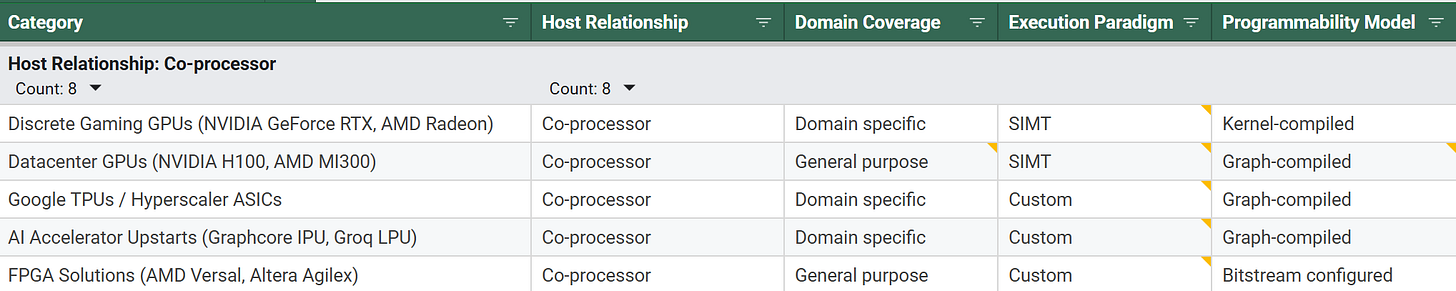

Taken together, these questions offer a better way to think about modern compute architectures. Once you look at chips through these lenses, debates like GPU vs TPU vs NPU start to feel oddly shallow. Architectures stop being mysterious, and performance claims start to look like the predictable outcomes of very specific tradeoffs. For instance, below is a classification of several chips that are often loosely grouped under the label “accelerators.” This classification forces each architecture to reveal its position along concrete design axes: who controls the system, how broad the user base is, where throughput actually comes from, and how programmers interact with the hardware. Chips that are often lumped together as “accelerators” end up in very different places once you apply these questions, and those differences explain far more about real-world impact, adoption, and longevity than any three-letter acronym ever could.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, here’s a reason to: when you subscribe, you’ll receive the link to the full list with other categories and explanations.

If you have read so far, I’m curious - what other questions would add value to chip architecture classification?

Excellent breakdown on why the PU acronym game has gotten out of hand. The host relationship framework is particularly useful becaus it cuts through so much marketing noise. I've been working with systems where the differenc between co-processor and integrated IP determines whether a workload even makes sense, and that's never captured in benchmarks. One thing I'd add is power budget constraints as a fifth axis, especially for mobile and edge deployments where thermal limits can completely reshape which architecture wins regardless of peak throughput.

Didn't expect this take on processors! Reminds me of your node naming insights. Very clever.